This is, in some ways, a follow-up to my article talking about how China is not a superlatively old civilization. For various reasons related to contemporary politics, language barriers, the development of archaeology, and the course of 20th-century historiography, grandiose claims that inflate the historical accomplishments of Chinese civilizations are commonplace in both online discourse and, unfortunately, serious historical work.

From 1405 to 1433, the Ming Empire carried out a series of seven long-distance maritime expeditions. What you should know:

These expeditions were truly impressive for their time.

While they showed the Ming Empire to be arguably the most powerful oceanic naval power of the early 1400s, they are often overstated.

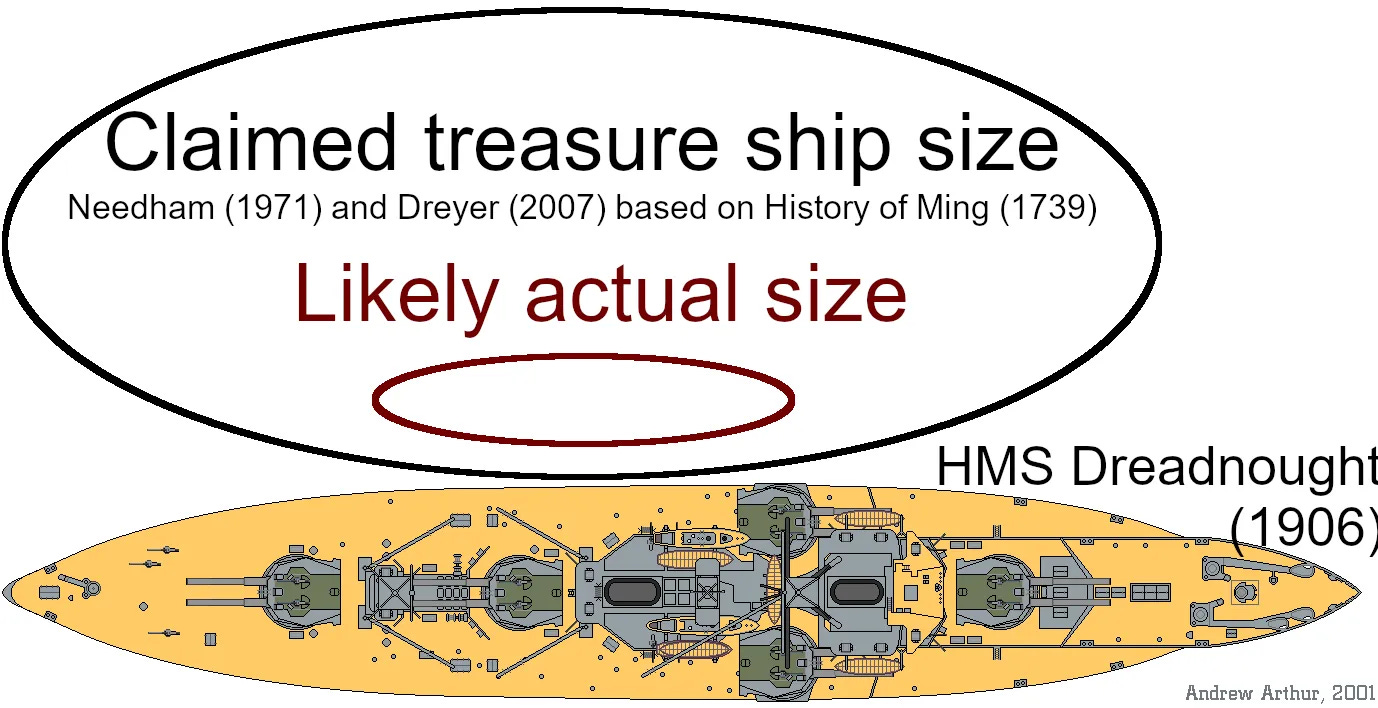

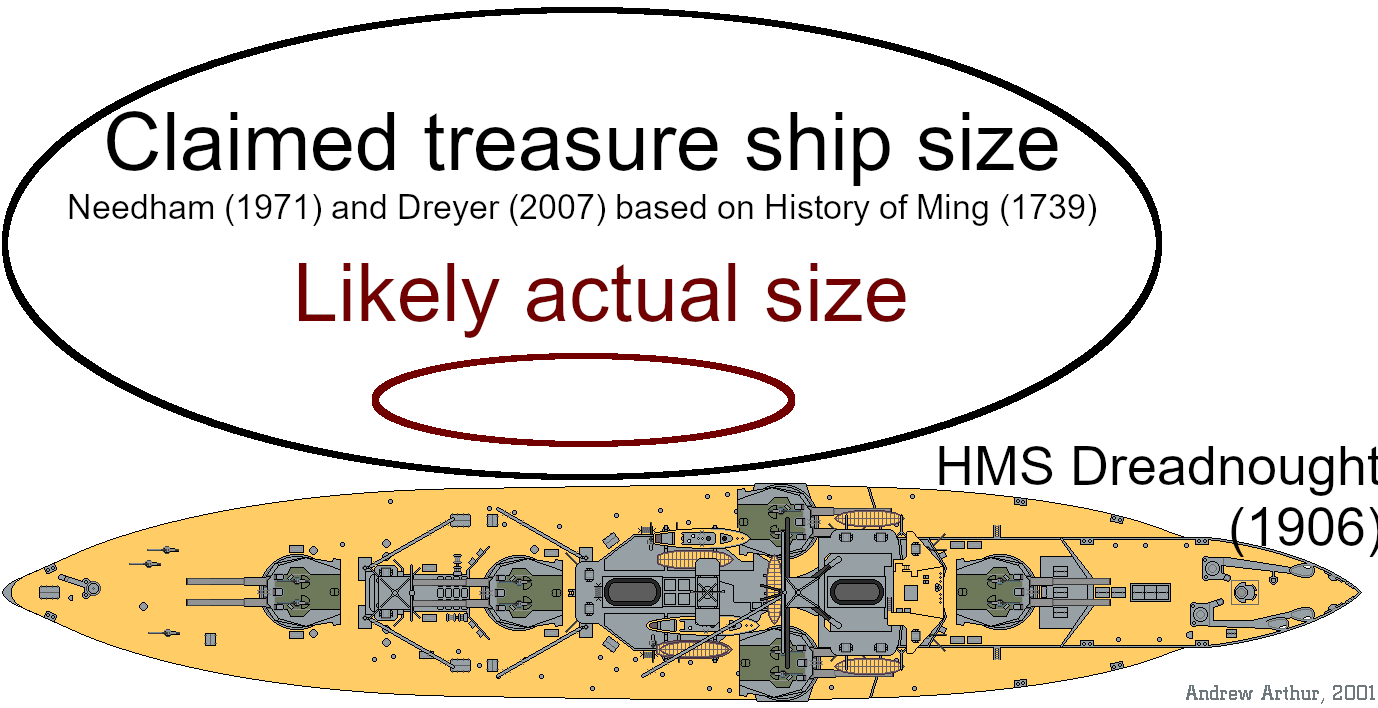

The “treasure fleets” were genuinely impressive armadas for their time, including ships that were larger and arguably more sophisticated than contemporary European sailing vessels. However, the size of the treasure ships appears to have been dramatically inflated in subsequent histories to make them comparable in size to the HMS Dreadnought and other early 20th-century steel battleships, measuring 450 feet long and displacing upwards of 20,000 tons.

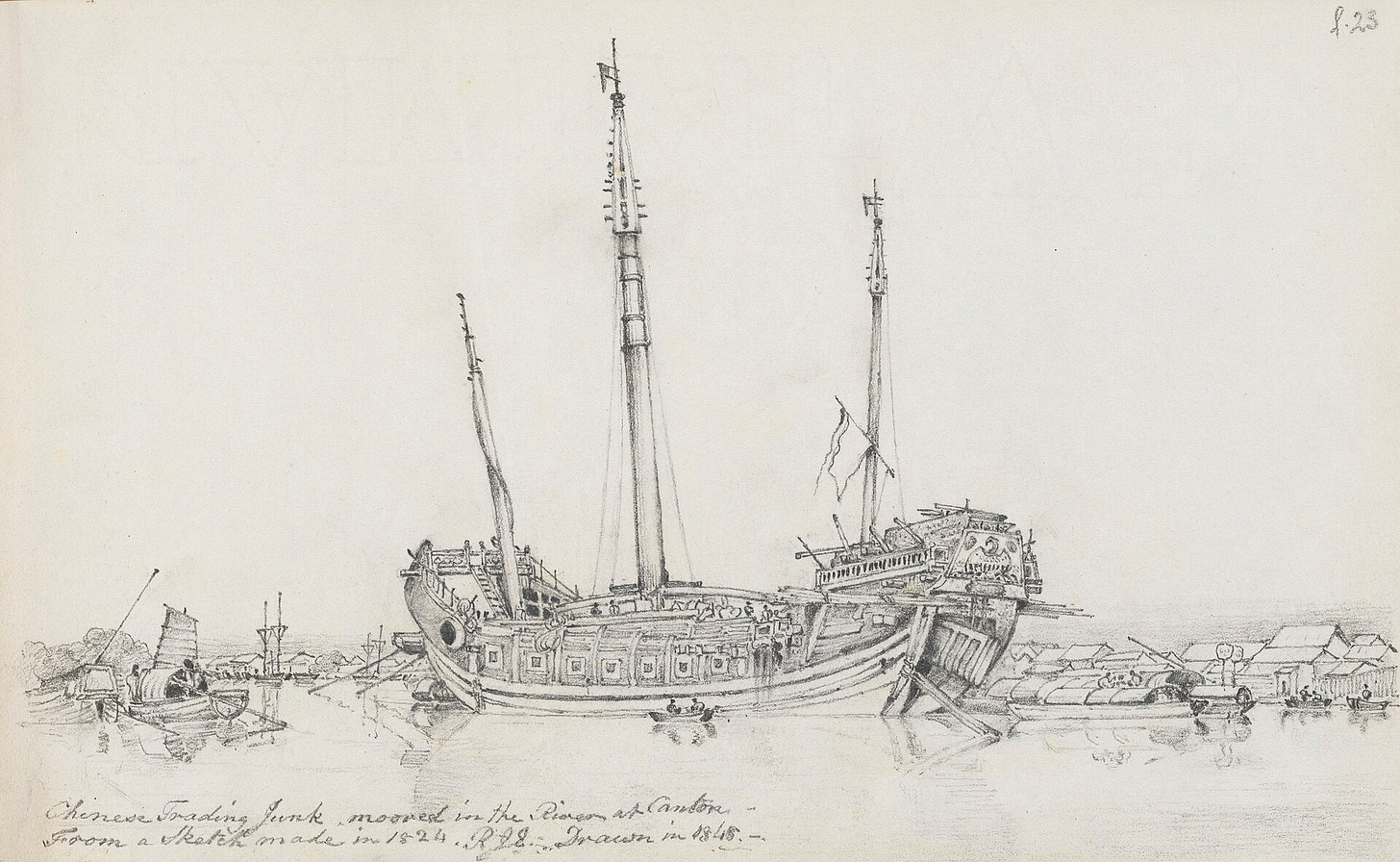

Based on contemporary accounts and engineering constraints, Zheng He’s treasure ships were unlikely to be any larger than many of the better-documented oceangoing junks of the 1800s, which measured 160 feet long and displaced on the close order of 1,000 tons.1

This still made Zheng He’s expeditions incredibly impressive: His fleet was comparable in size to the Spanish Armada, traveling distances comparable to those traveled by Magellan.2 However, while the fleet and voyages were genuinely impressive feats that suggest the Ming were the most impressive empire of their day, subsequent Chinese accounts, including some accepted modern Chinese scholarship, inflate the size of these ships.

The size of the crew

Unlike the size of the ships, the number of men under Zheng He’s command and the number of ships involved in each expedition is generally not considered a subject of great controversy.

Most available sources roughly agree on the numbers of personnel involved, with similar figures of 27,000-28,000 personnel for the expeditions,3 with dozens of treasure ships and hundreds of vessels in total. While Wikipedia assumes that treasure ships get larger with the fourth expedition, the common cited figure for the number of treasure ships (62-63) and total expedition personnel (27,000-28,560) are very similar for the two expeditions.

As a point of comparison, the famous Spanish Armada sent to crush the English included 24 warships, 137 total ships, and 29,000 personnel, if we do not include the barges full of soldiers manned by the Spanish Netherlands.4 The largest ships of the Spanish fleet had a displacement of around 1300 tons and carried a little more than 400 men into battle.

With a total of 450 personnel per treasure ship, including the crews of support ships, it seems unlikely that the treasure fleets were much, if any, more massive than the Spanish Armada.5 The personnel counts given in later sources are not only generally non-controversial on their own merits, but line up very neatly with contemporary sources: Gong Zhen, who served as Zheng He’s secretary 1431-1433 during the final expedition, said that the treasure ships required 200-300 sailors each. Various other specific accounts place between 120 and 300 men on specific ships during specific incidents.

Contemporary accounts of the size of the treasure ships

Direct contemporary accounts of the size of the treasure ships are limited. A stone inscription at the Jinghai temple with historic links to Zheng He says that he commanded 2000-liao ocean-going ships in 1405 and 1500-liao ocean-going ships in 1409, along with “eight-oared” ships, presumably smaller support ships.

Finally, Niccolo de Conti, a Venetian explorer contemporary with Zheng He, writes that he encountered large ships “capable of containing 2,000 butts in size,” i.e., an estimated cargo capacity of 1,300 tons.6 This is particularly noteworthy because, based on time and place, it seems plausible that de Conti may have witnessed one of Zheng He’s later expeditions.

The liao may be a unit of capacity, volume, or displacement. It has been estimated variously as 400-1,000 pounds, but one likely figure is a quarter ton.7 The cargo capacity of ships is also related quite closely to the crew and handling requirement. A 2,000-liao treasure ship would probably have a displacement of around 800 tons, comparable to the mid-sized naos of the Spanish Armada that carried 200-300 people into battle.

There is also a contemporary source discussing the crewing of Ming Empire ships. Song Li, the contemporary Minister of Works (1405-1422), described sea-going grain transports as carrying 1,000 units of grain for a crew of 100, which is a ratio of 10 units of cargo per crewmember; this makes it very plausible that the complements given of 200-300 men, including soldiers, diplomats, and court officials, corresponded to 1,500-liao or 2,000-liao ships.

The mass of available evidence from contemporary sources points to Zheng He’s ships being comparable in size to the Keying, a late-generation (19th century) Chinese junk that was sailed all the way to the United States.8 They could have been a bit larger or smaller, but at least some of them were likely in the same ballpark of size.9

Bigger ships, bigger problems

The widely-cited dimensions for the treasure ships appear to originate with a 1597 novel, whose author was born more than a hundred years after the expedition. The figure of 44.4 zhang, or 444 feet, is implausibly large.10 Since the number 4 is considered particularly auspicious in Chinese numerology, this number was likely pulled out of thin air by a novelist with no knowledge of shipbuilding and no specific information about the actual physical size of Zheng He’s ships.

It is very difficult to build seaworthy wooden ships with a displacement of much over 1,000 tons, and difficult to increase the size of ships substantially without significant changes in techniques and technology. The Swedes, generally skilled shipwrights, famously failed completely with the 1,200 ton Vasa in 1627, which sank less than a mile into its maiden voyage. The largest sailing ships of the 1800s required metal reinforcement of their hulls.

Keels and masts usually are made from a single tall tree, which puts natural limits on the length and height of a wooden ship using the same building techniques as were available to the Ming, limits closely related to the availability and size of high-quality trees.11 All the structural constraints related to ships become more difficult for ocean-going ships intended for long voyages over rough seas.

As the 600th anniversary of Zheng He’s voyage approached, there was interest in China in building a functional replica of a treasure ship. A 230 foot replica was designed with a displacement of 3,100 tons. In spite of ample funding and the patriotic nature of the cause, it was never finished and never launched. Personally, I suspect that the design was not seaworthy.

Recap and review

From an engineering perspective, the claimed “44.4 zhang” length of the treasure ships is absurd. From a logistical perspective, the idea that a fleet of sixty sailing ships the size of HMS Dreadnought (complement 700-800) accompanied by a couple hundred smaller ships could be adequately manned by 27,000 soldiers is likewise absurd; the same sources that claim a large size for the treasure ships also indicate they had a crew of 200-300 men each.

Further, the length of 44.4 zhang first appears in a work of fiction and, based on traditional Chinese numerology, looks like a fictitious number chosen for symbolic reasons. Contemporary sources seem to point to a much smaller size, with a displacement of 500-1,300 tons or so. Finally, unlike contemporary attempts to reconstruct historic longships, triremes, and other historical ships, no attempt to build a seaworthy treasure ship has yet succeeded.

Instead, the famed treasure ships of the Ming were very likely similar in size and functionality to the ocean-going ships under Mongol rule (Yuan) and later Manchurian rule (Qing). Any one of the treasure ship expeditions was similar in overall size to the Spanish Armada, traveling a significantly longer distance more than a century earlier.

Considering the combination of distance, scale, and repetition, this was one of the most impressive feats of naval logistics prior to the Napoleonic Wars. The expeditions make a strong case for the Ming being the premier world power of their time; however, the claims of four hundred foot treasure ships dwarfing any other sailing ships ever produced should not be taken at face value.

These are, for example, the dimensions of the Keying and the Tek Sing, both of which had an estimated capacity of around 700-900 tons. The treasure ships most likely had a rated capacity of 500 tons, although there is wiggle room in that. This article echoes, to a large degree, the arguments made in this 2005 article (by S. K. Church, published in Monumenta Serica, Volume 53, pp. 1-43).

Granted, Magellan’s circumnavigation of the world was still an impressive first, but the Red Sea is about halfway around the world from northern China.

Personnel figures are usually cited for the 1st, 3rd, 4th, and 7th expeditions.

The English fleet only had 16,000 men aboard, but had 34 first-rate warships.

Ratio of tonnage to personnel is not a universal constant, but it is likely to be crudely similar.

Wake (1997) gives the Venetian butt as being about 1,300 pounds, making 2,000 butts equivalent to 1,300 tons.

This is the figure used in my principal reference, and also the one the Wikipedia editors settled on in the contentious Wikipedia article on the topic. It is known that there were 90 foot military ships rated at 400 liao. The Shinan ship, which speculatively may have been one of the “standard” 1000-liao sea-going cargo ships spoken of in Ming records, had an estimated cargo capacity of 200 tons.

If the liao corresponds to a quarter ton of capacity, then the more modern Keying was approximately a 3,000-liao ship, while if the liao corresponds to half a ton of capacity, then the Keying would be a 1,500-liao ship. Sleeswyk’s volumetric calculation, using the liao as an estimate of total displacement, could put the Keying around a 2,000-liao size.

Taking de Conti’s “2,000 butts” estimate as a precise face value, the treasure ships would have about 60% more cargo capacity. Taking the 500 pound liao at face value, the treasure ships would have about 60% of the cargo capacity, i.e., the treasure ships were 60%-160% of the size of the Keying.

That is, 444 Ming chi, a unit reasonably translated as “foot” based on similarity in size. Like many other “foot” measures, the Ming chi was not standardized, but approximately 10-13 inches or so depending on exactly where one was within the Ming Empire.

The Swedes famously planted an entire forest of oak trees for future use as masts in 1830. They are now ready for harvest, although the Swedish Navy appears to have no intention of taking advantage of this bounty.