China is not ancient

It's old, but not superlatively old, and some parts are very new.

One of the pieces of misinformation I consistently run into online is the notion that “China” or “Chinese civilization” has a uniquely ancient history, with broad scope in both space and time. Since I’m tired of repeating myself, I’ve decided to put a quick summary treatment of the topic in one place.

The short and fully correct answer: By Old World standards, Chinese history is neither unusually short nor unusually long, neither unusually continuous nor unusually discontinuous. Nor is it clear that China developed civilization independently from the West. What makes Chinese culture and history exceptional is its human scale, i.e., the sheer population that can be identified as belonging to a Sinitic culture or polity.

A brief history of history

History is based on the written record of events, while archaeology is the study of the physical remnants of human society. Early written history frequently includes reference to prehistoric events and blends seamlessly into mythology, especially regarding lineages. The Sumerian Kings List, the Book of Genesis, and the Chronicles of Japan, for example, all include highly unrealistic lifespans for prehistoric leadership figures that blend seamlessly into creation myths.1

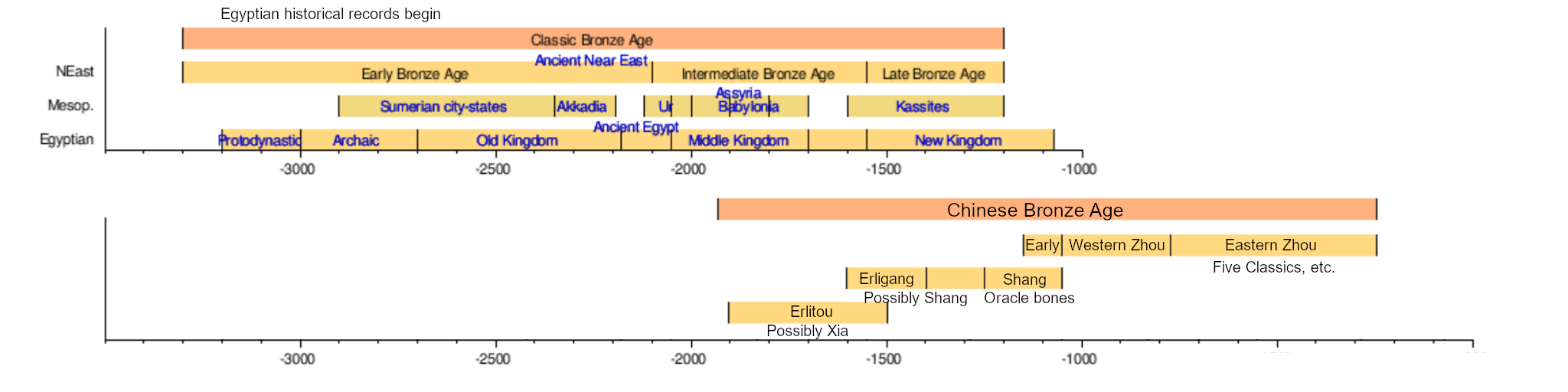

In Mesopotamia, Egypt, and arguably the Indus Valley, writing appears around 3000 BCE; in the case of Mesopotamia, this is preceded by roughly 5,000 years of gradual development of symbols used for accounting purposes.2 Many ancient scripts were forgotten, although some have been deciphered in modern times.3

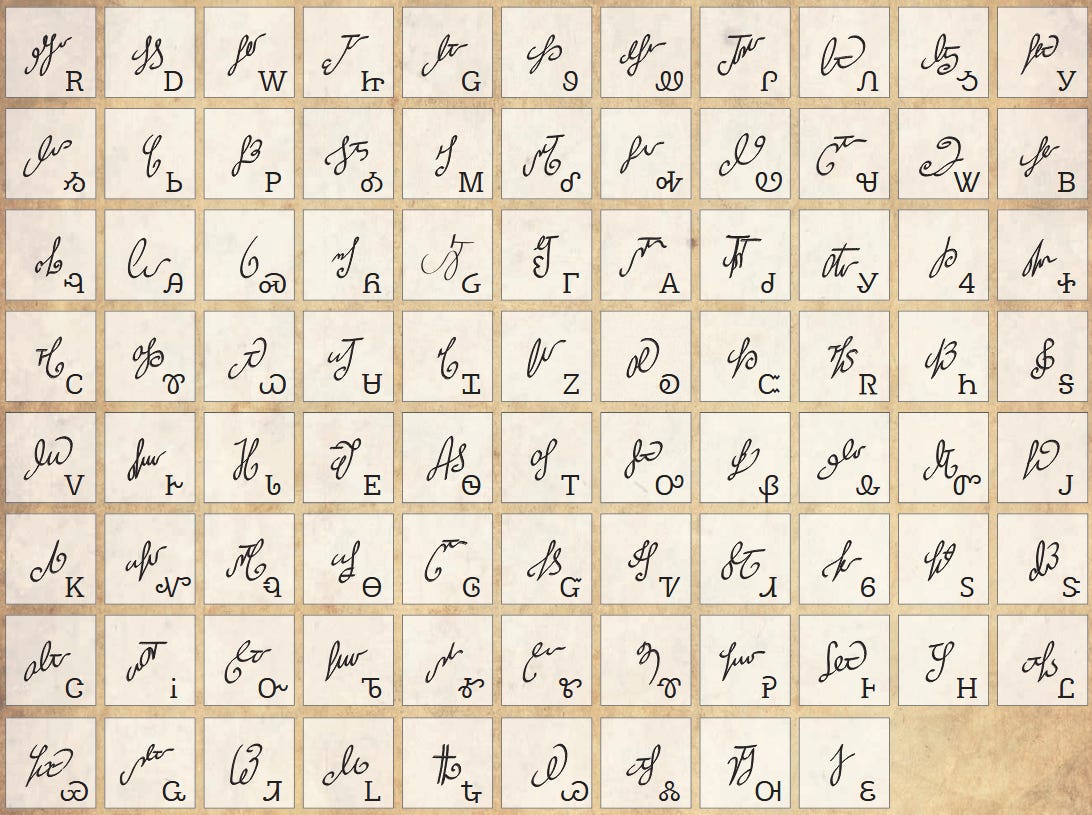

In China, the earliest known examples of writing date from around 1250 BCE, most of the oldest examples of Shang script being preserved on oracle bones with some on bronze inscriptions.4 Like cuneiform and hieroglyphs, the art of reading the Shang script had been forgotten. A majority of Shang logograms remain undeciphered today. There are two things worth noting about Shang logograms that I will circle back to: First, they show a large amount of stylistic variation. Second, they are not preceded by related protowriting.5

Invention and imitation

Early historians frequently overlooked how mobile and connected the ancient world was. Neolithic trade routes show the movement of lapis lazuli and obsidian across thousands of miles; during the Classic Bronze Age, Cornwall and Devon exported tin all the way to the eastern coast of the Mediterranean. Neolithic trading networks appear to have existed across what is today China before the beginning of the Chinese Bronze Age; the earliest date for plausible transmission of bronzeworking technology from the West to China is over a thousand years before the actual beginning of the Chinese Bronze Age.

Furthermore, bronze artifacts appear first in what is today Xinjiang and work their way westward over time. In other words, bronzeworking was not independently reinvented in China, but instead brought from the West, along with ironworking, chariots, and domesticated horses.6 The main notable technological exception is pottery; the later neolithic and chalcolithic Chinese civilizations have pottery as advanced as their contemporary chalcolithic and Bronze Age counterparts in the west.

The sudden appearance of the oracle bone script could very easily be a case of transmission of technology as well. Oracle bone script appearing quite suddenly with the Shang in a sophisticated but nonstandardized form that evolved very rapidly fits perfectly with the possibility that the oracle bone script was not truly an independent invention, but developed through Bronze Age contact with civilizations that had writing systems.

Since independent invention of writing is rare, this is generally presumed to be the case with logographic systems from civilizations known to be in trade contact with writing civilizations, such as Cretan hieroglyphs.7 The knowledge that Shang oracle bone script postdates the development of trade networks connecting Bronze Age China to Bronze Age civilizations with writing technology should generate a similar presumption. After all, it takes only one intelligent person to invent a writing system once they are aware of the possibility.

In 1809, Sequoyah, an illiterate Cherokee man, was impressed with the “talking leaves” of the white men and decided that the Cherokee needed something similar. In the span of twelve years, he first attempted to create a logographic language, and then switched to a phonetic language. He used written examples of English and Hebrew as inspiration for the shape of the symbols, though he did not know or use the phonetics of the English alphabet.8

One of the more peculiar scripts of the world is rongorongo, used for some time on Easter Island. Notably, the Easter Island civilization appears to have only existed for about 600 years, which is a brief period in which to independently develop writing. It may have been rapidly invented after Easter Islanders witnessed Westerners using writing.

Whether or not this is true, what rongorongo and the Cherokee syllabary demonstrate is that relative to ancient archaeology, a relatively mature writing system can develop quite rapidly once someone brings the idea of writing into a civilization. The original invention of writing appears to have taken thousands of years of incremental evolution; but the mere presentation of the idea of writing brings the creation of a new writing system within reach of a single enterprising individual.9 I would go as far as to say that it is more likely that the Shang were not among the first six Eurasian civilizations to independently invent writing than that they were the third.10

It is sometimes said that the oracle bone script appears remarkably mature on its earliest appearance; however, the same could be said of rongorongo and the Cherokee syllabary. Given the presence of a network of trade routes that could be traversed by a single person in both directions within the span of a decade, it is not remarkable that the idea of writing would reach the Yellow River valley within two thousand years of indirect trade with literate civilizations.11

Early historians and archaeologists underestimated the degree to which the ancient Eurasian world was connected by trade. Given what we now know about how connected the ancient world is and the ease of transmission of ideas, the notion that any Eurasian civilization or technology emerged significantly later than the earliest examples ones but fully independently should be considered highly questionable a priori.12 This is not considered controversial in the case of European civilizations.

Cultural heritage

In the above, I’ve laid out the case that Chinese civilization belongs to a later generation of early Eurasian civilization, with key technologies being likely transmitted rather than developed independently. With respect to civilizational and cultural continuity and development over time, “Chinese civilization” is a similar concept to “European civilization,” referring to a series of politically and culturally distinct political entities that share some level of common cultural heritage and technological transmission.

The oldest extant works of literature in China are the Five Classics. Purportedly compiled or authored by Confucius or his students circa , this includes documents and speeches supposedly from the Western Zhou era (1046-772 BCE), a contemporary history of Confucius’s home state from 722-481 BCE, a book of poetry, a ritual book, and the famous divination manual, the I Ching. Some portions may have been authored as late as 200 BCE.13 It includes narratives that stretch back to the [possibly mythical] Xia kingdom.14

In other words, the Five Classics are similar in age and uncertainty of provenance to the Odyssey and the Pentateuch, which are important parts of the Western cultural and religious canon, respectively. Also similar to those most ancient parts of the Western canon, they were originally written in a very different script and in a language quite different from any of the modern Chinese languages.

The Epic of Gilgamesh and the Book of the Dead are considerably older, representing the unearthed lost cultural heritage of the world’s most ancient known literate civilizations. There is no reason to call the Chinese classics a deeper and more ancient literary tradition than the Greek or Hebrew classics, though one could contend greater antiquity on the Western side on the basis of the influence of Sumerian and Egyptian culture on classical Greek and Hebrew work.15

Continuity and history

Some confusion arises on both sides because cháo (朝) in the context of Chinese history should not really be translated as “dynasty.” Cháo is regularly used in ways that the word “dynasty” would not be used by a native English speaker, such as “proclaim a cháo.” Or having a single generation cháo such as the Xin cháo; a dynasty refers to a sequence of multiple related rulers.

Nor does cháo refer to the whole sequence of related rulers holding the same throne. Take, for example, the Shang and the Zhou. The Shang kingdom had a capital at Yinxu, a city north of the Yellow River. The Shang had some very distinctive cultural practices that did not survive their fall, notably a great fondness for human sacrifice. It was ruled by kings from the Zi family. In ordinary English parlance, Shang was ruled by the Zi dynasty.

Zhou was a separate kingdom with a capital on the Wei River, a southern tributary of the Yellow River. It had its own throne and a line of related kings that paid tribute to Shang: The Ji dynasty. But for Chinese historians, these first few kings are the pre-cháo Zhou. Instead, the kingdom of Zhou became a cháo in 1046 BCE after inflicting a military defeat on the Shang kingdom. The current Ji king of Zhou did not seat himself on the existing Shang throne; instead, he built a new administrative center on the opposite bank of the Wei River and kept living in the same royal residence. The Zi dynasty continued to rule the Shang kingdom, paying tribute to the Ji king as an emperor.

A closer translation to cháo as used for the Shang cháo and subsequent Zhou cháo would be “empire.”16 Cháo doesn’t really mean “dynasty” in English; it refers to an imperial mantle and is linked to the concept of tiānmìng (天命), usually translated as “mandate of heaven.”17 At times, multiple kings claimed the mantle of cháo for their kingdom in the same way that multiple European leaders have claimed the title of “Caesar” or the mantle of Rome.18

Athens has been continuously inhabited for over five thousand years (3000 BCE or earlier). It entered historical records as a Mycenean Greek city by the purported prehistorical beginning of China’s Shang era (1600 BCE), several centuries before the Shang began to use the oracle bone script. There is no city in China that can claim greater antiquity or cultural continuity than Athens.

Based on the archaeological record, Rome has been continuously inhabited since at least 1750 BCE, as long as any city in China, with claimed roots in the truly ancient Trojan civilization.19 Its official founding date as a polity, 752 BCE, predates that of China’s fifth-oldest city and compares with the creation of the Eastern Zhou cháo.20 The Roman polity was the European version of a cháo for longer than any Chinese equivalent.21 Viewed as a combined unit with shared cultural heritage, Greco-Roman civilizations were easily as continuous as contemporary Chinese civilizations from the Mycenean era to the Roman era, with fewer shifts in major power centers and dominant subgroups.

Jerusalem has been continuously inhabited since around 3000 BCE. It is attested to in the historical record as a city as early as 2000 BCE, prior to the settlement of China’s first prehistoric bronze age city. The Israelites are attested to in the historical record as a distinct group as early as 1208 BCE, predating the Zhou kingdom.

There are certainly major cultures and civilizations that are substantially newer or less continuous, and areas that cannot claim ancient civilizational roots. The United States is certainly not ancient, and can at most be considered a physically distant young offshoot of the older European civilization. Few American cities are more than a few centuries old.

Most Muslim cultures sharply disconnected themselves from pre-Islamic culture; since Islam was founded during the period of the Tang cháo, a thousand years after Confucius, it is significantly younger than Chinese civilization. The longest continuously-inhabited village in North America, Oraibi, was founded around 1150 CE, when China and Europe were already old. The Māori arrived in New Zealand around 1300 CE.

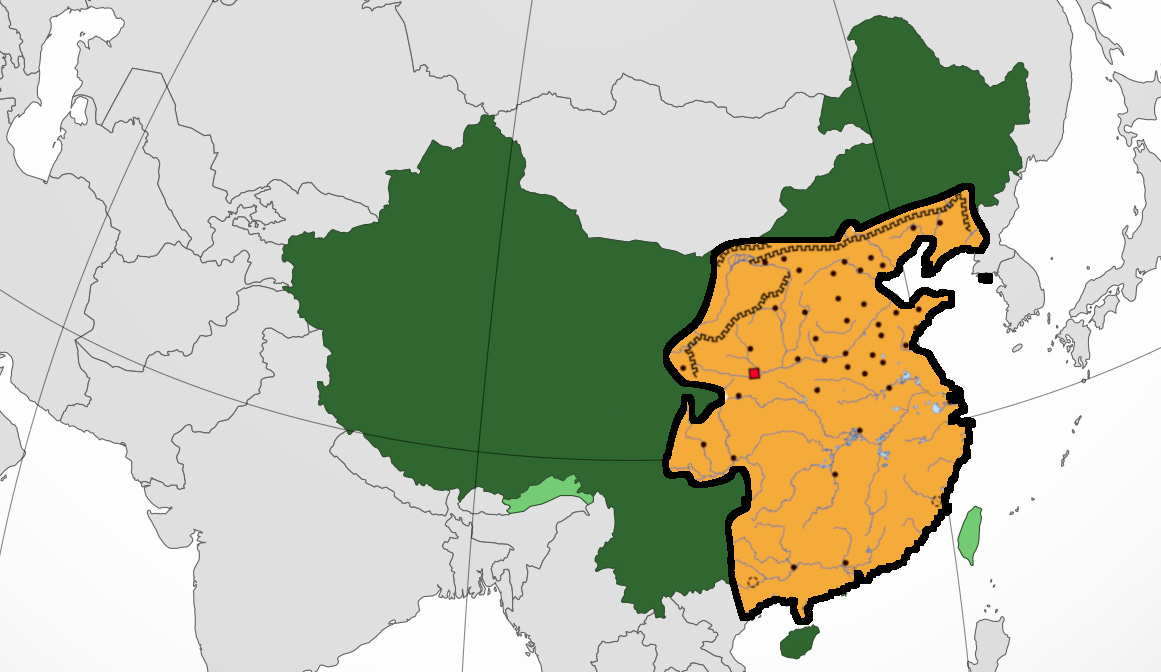

Modern China

The actual borders of modern-day China include lands that were not tributaries to any empire that included Chinese people until the conquest of China by the Mongolian Empire in the 1200s. The claimed borders of modern-day China include Taiwan, which was not a subject of any such empire until the Manchu-led Qing Empire in the 1600s. The territorial claims of today’s China are not very ancient at all, and are quite substantially larger than the area covered by the empires of Zhou or Han.

The People’s Republic of China that we see on the map today is a highly modern construction, with unusually expansive borders and an unusually ethnically and linguistically uniform population compared to the historical range of indigenous cultural and linguistic diversity in that area. But it is not unusually deeply connected to the ancient past; Europe has similar connections to its own ancient past. Like China, some parts of Europe are more deeply connected to a more ancient European history than others.

A stronger (but still contentious) claim to the oldest living civilization is held by India; while the antiquity of Hinduism is contentious, it remains plausible that Hinduism represents a continuation or fusion of the traditions of the truly ancient Indus Valley civilization, which dates back to c. 3000 BCE. For most civilizations older than the Indus Valley civilization, notably Mesopotamian and Egyptian, we have historical records documenting the replacement and extinction of their original cultural heritage.

China as a place is particularly notable not because it has unusually ancient heritage and traditions, but because it has been at the center of some very large-scale polities that endured for a significant length of time. There are times when the largest, most populous, or most powerful polity on the planet has been one centered in China.

Of these, the Sumerian Kings List is the oldest and also the most egregious offender, with a chronology spanning hundreds of years

Clay bullae date from around 8,000 BCE. Sumerian writing is thought to be the older of the two, but writing may have emerged independently in both places.

Hieroglyphs and cuneiform in the 1800s,

Early use of symbols (“proto-writing”) can be found in earlier civilizations. Sumerian bullas date back to about 10,000 years before present, with proper cuneiform writing appearing about 5,000 years ago.

Potentially symbolic inscriptions have been discovered in pre-Shang archaeology, but unlike Sumerian accounting tokens or pre-hieroglyphs in Egypt, there is no clear connection. In the current archaeological record, the Shang oracle bone script appears very suddenly and in substantial quantity. Nor are the symbols as consistently repeated and complex as other proto-writing identified, such the Indus script, which is frequently thought to be proto-writing but may have been writing that was preserved only through extremely limited examples.

This is widely supported by extant research, although underemphasized and generally politically inconvenient for the CCP’s preferred Chinese historiography.

Cretan hieroglyphs predate Shang oracle bone script by about 1,000 years and postdate Egyptian hieroglyphs by around 1,000 years. A small number of symbols are (perhaps coincidentally) similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs, which is also true of Shang oracle bone script. Nevertheless, since contact is presumed to exist, Cretan hieroglyphs are not presumed to be an independent invention of writing. Chinese silk was reaching Egypt in small quantities as far back as 1000 BCE, although there were many closer civilizations with writing technology by the point of the earliest recorded Shang oracle bone script examples.

For example, the letter “A” in the Cherokee syllabary corresponds to “go” or “ko” and the letter “M” to “lu.” The Cherokee syllabary also uses syllables as a base unit (like hangul or katakana) rather than root phonemes, the result of which is that it includes 85 symbols.

Even with Egyptian hieroglyphs, which emerged as a writing system two thousand years before oracle bone script and shows no direct morphological relationship to Sumerian cuneiform, scholars continue to question whether or not the script was developed independently or inspired by the Sumerian writing system in spite of hundreds of years of visible evolution of closely related protowriting symbols.

The Shang oracle bone script’s case for complete independence is not very strong, for reasons outlined above: It comes two thousand years after the earliest plausible date that a trader could have come and told the locals about the “talking tablets” of ancient Sumer. On the other hand, there are a large number of candidate scripts and proto-scripts that could, in fact, represent independent Eurasian inventions. They are symbolically as distinct from cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs as the Shang oracle bone script. This includes the undeciphered Indus script, Cretan hieroglyphs, proto-Elamite (Jiroft) script, the Vinca script, et cetera.

For example, Marco Polo’s famous journey started in Italy and reached Kubilai Khan’s palace four years later, including a similar land route likely similar to what would have been used by Bronze Age traders. It is certainly possible to walk from the Tigris and Euphrates to the Yellow River in less than five years.

Given the fact that Çatalhöyük, arguably a city and widely considered at least a protocity, was settled at least 9500 years ago, it’s not clear that the social technologies involved with the development of cities were invented more than once in all of Eurasia. Scholars have gone back and forth over the years over whether Eurasian civilization emerged once in the Fertile Crescent or multiple times. In the case of Egypt and the Indus River Valley, the antecedent presence of protocities and protowriting that temporally overlap the protocities and protowriting of Mesopotamia have provided a more convincing case for independence.

The Qin empire (221-206 BCE) had a tumultous and swift rise and fall, which was very destructive for the physical records, and both the Qin and the succeeding Han empire had a strong interest in rewriting history. The Book of Rites in particular is said to have been “reconstructed.” Some portions of versions of the Five Classics that carbon date to before the Qin dynasty (c. 200-300 BCE) have been recovered.

Since only the latter nine Shang kings were contemporary with writing, it is possible (though unlikely) that all but the last nine Shang kings were fictional. However, king lists frequently do reach into fictitious territory as they reach into prehistory, so some skepticism on the length of the Shang dynasty is warranted, and the existence of the Xia as such remains somewhat questionable. Ancient historians do sometimes prove right even when their claims seem unusual to modern historians, however, so it should not be presumed the Xia were entirely mythical, either, though no Shang inscriptions have been found that confirm any discussion of the Xia prior to the Zhou dynasty.

The similarities of the Epic of Gilgamesh to certain biblical stories helped propel the discovery of the ancient epic into the spotlight in the 1800s, and Gilgamesh is included as a character in the Book of Giants. The relationship between Greek and Egyptian mythology is also a matter of considerable note.

“Empire” and “emperor” get translated questionably. Chinese history has a sequence of new inventions of superlative titles. It’s traditional to translate the one invented by Ying Zheng of the briefly-supreme Qin state as “emperor.” However, in normal English usage, a singular supreme ruler with vassal kings is an emperor.

Alternately, to use the English phrase, “divine right.” The main distinction is that European monarchs claiming a divine right

The titles of “tsar” or “kaiser,” for example.

The claims are largely considered to be about as mythical as the Zhou claims about the Xia, for the same reasons, but Troy was inhabited from around 3600 BCE, a walled city of note from around 3000 BCE, and sacked c. 1180 BCE. The inhabitants from 1750 BCE-1180 BCE were likely Luwian speakers.

Handan, 689 BCE.

By 146 BCE, Rome had conquered Greece and Carthage. The fall of Rome is conventionally dated to 476 BCE. This is a period of 621 years, and represents the one commonly accepted version of a timeline of the rise and fall of Rome.

If we combine the periods of the Western Zhou and Eastern Zhou cháos, the Zhou cháo is credited with a 789 year duration, but if then again, if we’re willing to include the Eastern Zhou after moving their capital east, we should also include the Eastern Roman cháo in the total for the Roman cháo.

Possible ending dates for the combined Roman cháo are various, including Charlemagne’s proclamation of a Holy Roman cháo in 800, the sack of Constantinople in 1204, and the final fall of Constantinople in 1453.