Why "The Great Gatsby" isn't all that great

It's a great piece of genre fiction - but not a true great classic. And it's not alone.

Since the late 1940s, The Great Gatsby has been studied regularly in American high school classrooms. Within America’s study of its own literary heritage, it is part of the literary canon. It is often referred to as a “literary classic” for that reason. However, it is not great literature in the same way that many other literary classics are.

There are two types of “literary classics” in our literature. The first type includes most of the older works of great literature in a variety of forms and formats, ranging from epic poetry (from The Odyssey to Beowulf) to plays (from Oedipus Rex to Hamlet) to novels (from Don Quixote to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn). The second type includes most of the “English class” books that everyone loves to hate.

This is a problem because it has become increasingly difficult to interest students in reading books, which has significant downstream effects in both the area of practical literacy1 and cultural continuity.2 And it’s not an age problem: The true classics are timeless. The problem is in selection: Picking good books is genuinely hard.

What is classic?

Since I am advancing a thesis that a number of people who believe themselves to be experts will find slightly controversial, it behooves me to pause to a moment to say precisely what I mean when I call a book “great” or “classic,” and how The Great Gatsby and many other direct-to-classroom specials fall short. Let’s start with a definition for classic:3

Classic (adjective): Having lasting significance or worth; enduring.

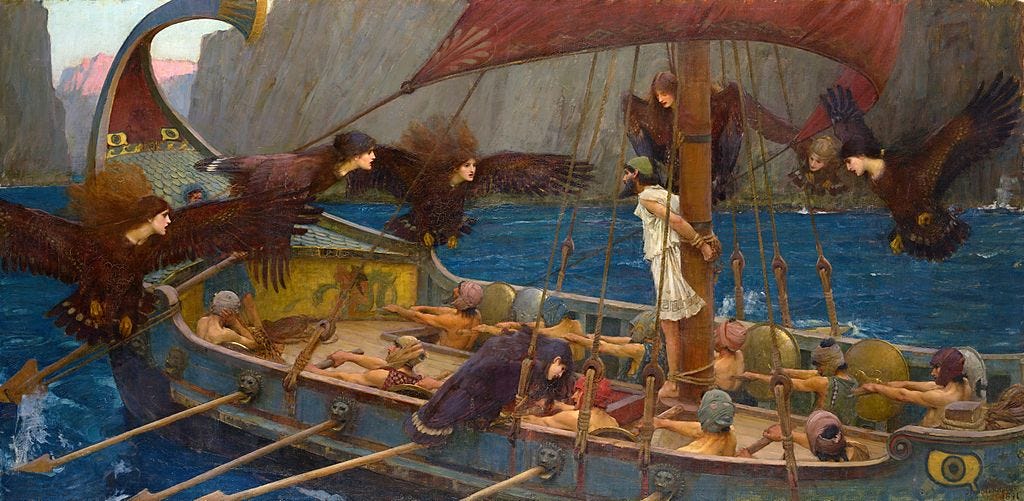

To be classic, a story needs to have lasting significance or worth and an enduring, timeless, quality. The Odyssey has connected with audiences for thousands of years. Its initial period of high popularity lasted for centuries, and it has had numerous revivals in interest since then. Its contents have continued to influence new writers for just as long. It is incontestably a classic.

And, in fact, almost every so-called “literary classic” written prior to 1900 or so needed to be popular for multiple generations in order to work its way into the canon of literary classics. The works of Shakespeare’s less-popular rivals have faded into obscurity or been entirely erased from the record.

What is great literature?

Many literary critics have divided books into “genre fiction” and “literary fiction,” or less accurately and more snobbishly, “real literature.” As an avid reader who has read more literary fiction or genre fiction than most of the more snobbish critics, I’m going to point out instead that genre is a property of all work, whether it’s highbrow or lowbrow:4

Genre (noun): A category of artistic, musical, or literary composition characterized by a particular style, form, or content.

Pride and Prejudice is generally considered “real literature,” but can be clearly categorized generally as a romance novel. We can get much more specific and say that it is a closed-door regency romance novel.5 This genre also defines a natural audience: Romance readers. What makes Pride and Prejudice largely considered “great literature” when 21st century romance readers are more likely to read Twilight?

Great (adjective): Markedly superior in character or quality

One common answer, functionally, is to say that experts in literature like Pride and Prejudice more than Twilight, but that answer is inadequate because it kicks the can down the road to the next “Why?” question: Why do experts in literature like Pride and Prejudice more? What defensible reasons can they give?

Pride and Prejudice speaks much more broadly to the human condition. Or, in other words, Pride and Prejudice transcends its genre more than Twilight. A broader variety of readers can enjoy, appreciate, and connect with Pride and Prejudice.6 In other words, great literature has a true breadth of appeal in a lateral sense (cutting across audience demographics), while classic literature has a true length of appeal in a longitudinal sense (cutting across different time periods).

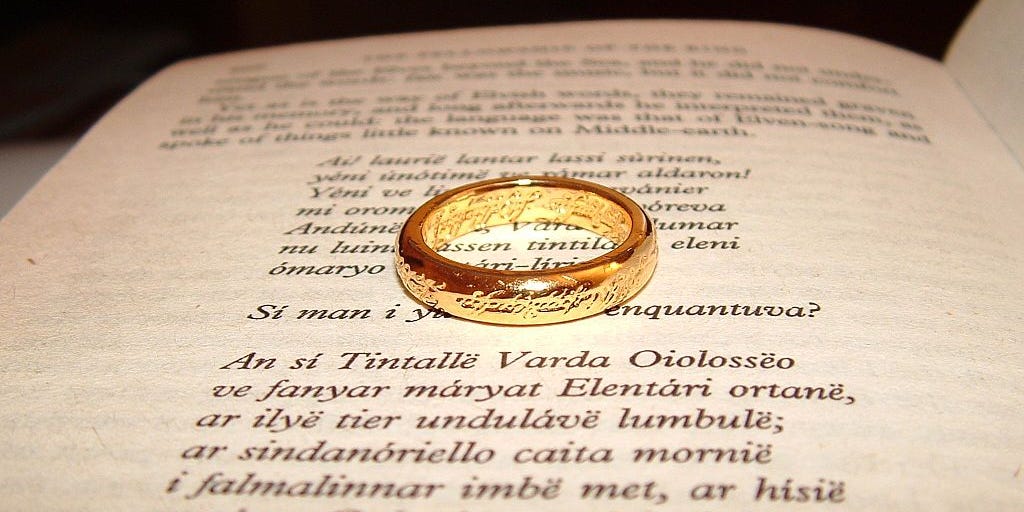

Great classics almost inevitably influence following literature. Shakespeare has inspired thousands of imitators. One of the major arguments for identifying Lord of the Rings as a great classic is the degree to which it has impacted the entire milieu of fantasy written afterward. The great classics are worth studying for their impact on the whole body of subsequent work.

What’s so great about Gatsby?

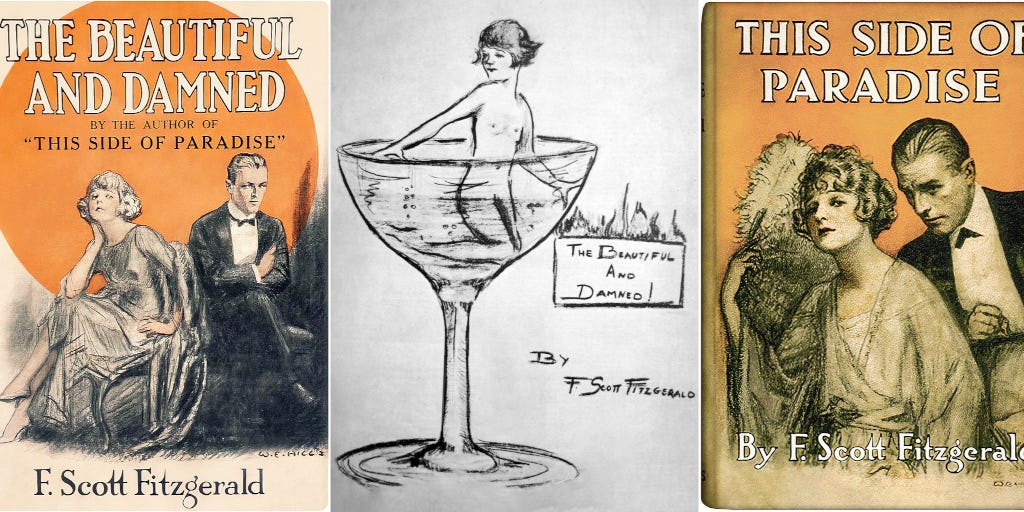

F. Scott Fitzgerald put out his first novel, This Side of Paradise, in 1920. It sold about 50,000 copies in twelve printings with good reviews from literary critics. His second novel, The Beautiful and the Damned, also sold about 50,000 copies. By the standards of the time, that was pretty good, though not astonishing, and there’s plenty of creative and literary talent on display in his work. But that’s true of a lot of authors.7

Then he wrote The Great Gatsby. Following wealthy Long Islanders in the party scene there, the story did well with New York’s wealth of literary critics, many of whom were very familiar themselves with the Long Island party scene.8 In terms of sales, however, it flopped, selling less than 25,000 copies. Fitzgerald then took a nearly decade-long break from writing novels, concentrating instead of short story and film.9 Copies from the initial two print runs of 1925 were still sitting unsold in the publisher’s warehouse all the way through Fitzgerald’s death in 1940. (Publishing practices were a little different back then regarding unsold books, see here for a discussion of that.)

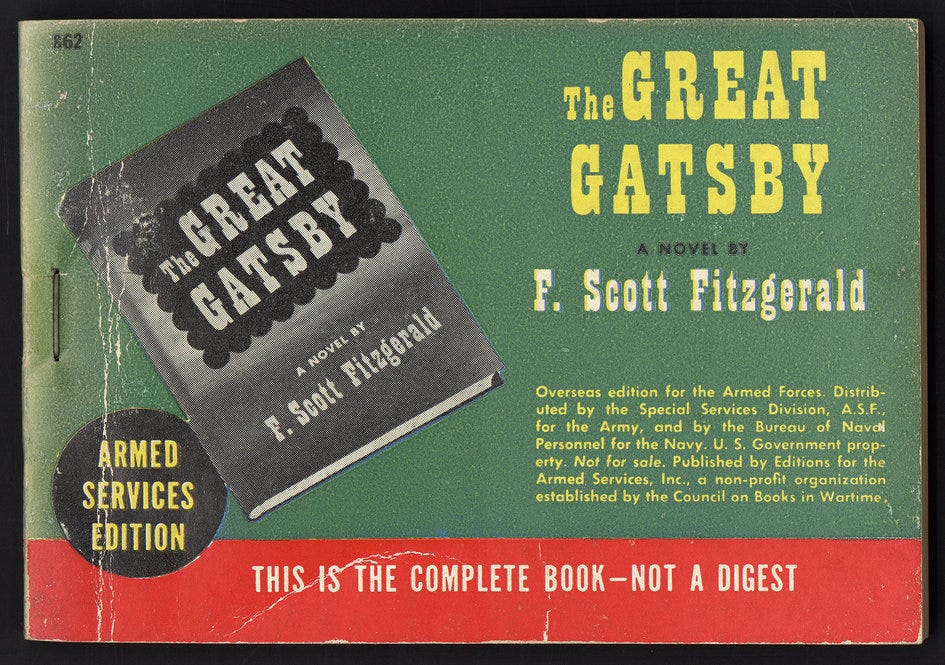

Following his death, Fitzgerald’s well-connected friends within the literary scene pushed for more recognition on his work,10 although he was no longer widely well-regarded.11 Thanks to the efforts of his friends, a group of wealthy donors and publishers printed up and donated 155,000 copies of The Great Gatsby to American soldiers during World War II, part of a selection of books that the donors thought would be edifying entertainment for the troops.12

This audience, as it turned out, included a number of future English teachers, and the book worked its way into high school English classrooms nationwide. From 1942 to the present, a large majority of all copies of The Great Gatsby have been purchased as the result of decisions made by persons other than the end consumer.13 As “literary classics” go, it was a direct-to-classroom special, with organic appeal to the overlapping circles of New York socialites, literary critics, English professors, and English teachers.

The Great Gatsby is very good litfic in the way that Fifty Shades of Grey is very good romance: It appealed quite strongly to a particular audience in a particular time and place. It is an excellent piece of genre fiction if you wish to study an example of the genre of 20th century litfic. Its cultural footprint, however, is limited to the icon of itself. It has had less impact on the litfic genre than Harry Potter, in spite of a seventy-year head start and the latter being in a totally different genre.

The American literary canon is in two parts.

To be quite frank, a lot of the American literary canon of the 20th century is similar to The Great Gatsby: It’s genre fiction with a narrow appeal, highly culturally and temporally specific, mainly marketed to the English classroom. It just happens that its genre is the one that goes under the marketing label of “literary fiction,” and so they are “literary classics,” not necessarily timeless but entrenched in a calcified curriculum.

In a more natural setting for literature, time tests works until they are forgotten or endure as classics. In the classroom setting or in professional literary analysis, the more frequently a work is taught or critiqued, the easier it is to further teach or critique, creating a vicious cycle where even mediocre work can become entrenched.

On the one hand, it makes sense for classrooms to be conservative and focus on proven works; on the other hand, this means that the curriculum can be increasingly irrelevant and stale to modern students.

On the gripping hand, the problem was that English teachers were picking the books they liked, and that continues to be a problem whether English teachers pick familiar “literary classics” within the litfic genre or whether they pick “contemporary fiction” that, while “up to date,” was written for and marketed to English teachers and has only a narrow genre appeal.

So, please: If you’re not picking a proven great classic, at least pick something the kids will enjoy. Better a book that you think is juvenile and shallow than something with lovely prose and deep symbolism that leaves them skimming the Cliff’s Notes or asking for a ChatGPT summary.14

Reading is a skill that improves with practice time. So is attention span. Reading books for fun trains both literacy and attention span.

Written text is our most durable touchstone and contains a lot of information, both in terms of facts and common metaphor. Streaming media is both highly fragmented and highly ephemeral.

This one is out of American Heritage.

This one is from Mirriam-Webster.

Not that it was originally marketed as “regency romance,” but a romance novel written during the Regency period and set therein certainly qualifies.

Future historians might disagree with this, but I think it’s fair.

Another hill I will die on: There’s a truly deep pool of talent, especially when you go back through history.

Worth noting that the US book publishing (and literature) scene revolved heavily around New York City at the time, and still does to a large degree.

His fourth and final completed novel, Tender is the Night, met with at best mixed reviews from the critics who had formerly been his most ardent supporters, and sold only 12,000 copies.

This extended to one friend in question finishing and publishing an unfinished manuscript of Fitzgerald’s.

Wartime service involved significant stretches of boredom, and the large majority of books included in the ASE program were met with ravenously appreciative audiences.

The end readers being, respectively, soldiers during WWII and students after WWII.

And it’s usually especially worth considering the boys, because both the publishing industry and the teaching industry lean heavily feminine and that really has made school reading lists a bit lopsided in terms of including a lot of books that don’t appeal to boys. But that side of the issue is worth its own article later.

What always annoyed me about The Great Gatsby, which I like a good deal more than most of those harshing on it online, is how it was taught to students as if it was this Hermetic Text with layers upon layers of meaning.

"What does the Green Light mean? Does it stand for Wealth? Envy? Daisy Buchanan?"

How about, "it's a pier light signaling there is room on the pier?" That might suggest a welcome invitation to Daisy, but there are other items that interested me more. For example, Nick notices that Gatsby has only read one of the books in his library. That IS a comment on class and education etc. That the one book Gatsby has read is The Autobiography of Ben Franklin matters even more, given how it parallel's what Gatsby is doing.

How do I know it's important? Is it because the book is some latent symbol? No. It's because it is expressly written about. It never ceases to amaze me how many people who pick up random things that Gatz does, and how they show he is modeling his life after Franklin, miss this moment.

The book has symbolism, but the green light is a green light.

Also, every kid who has to read The Great Gatsby should be allowed to watch Eight Men Out and The Sting.