Sometimes, I read romance novels, or watch shows based on romance novels. At times, I simply enjoy them. Every once in a while, though, I hit jarring moments where suspension of belief becomes difficult. Today, I’m going to focus on one I hit while watching Bridgerton on Netflix; a moment where I stopped, blinked, and said to myself: “I don’t know any men who act like that.”

The issue is the logic behind the “clever” ploy that kicks everything off: Daphne and Simon, professing a lack of interest in one another, decide to pretend to date each other in order to accomplish their mutual goals. This is supposed to accomplish two things:

It will help Daphne attract suitors, which is something she’s struggled with.

It will stop matrons from throwing their eligible daughters at Simon, who doesn’t want to marry at all and is an exceptionally eligible bachelor.

This plan succeeds on the face of it: Daphne gets more attention from other eligible men, and Simon experiences some relief. The plan only goes “awry” in the expected romance genre way: Both of them fall in deeply love with each other. However, the plan is a bad one, and its success strained my suspension of disbelief.

The social context of Bridgerton

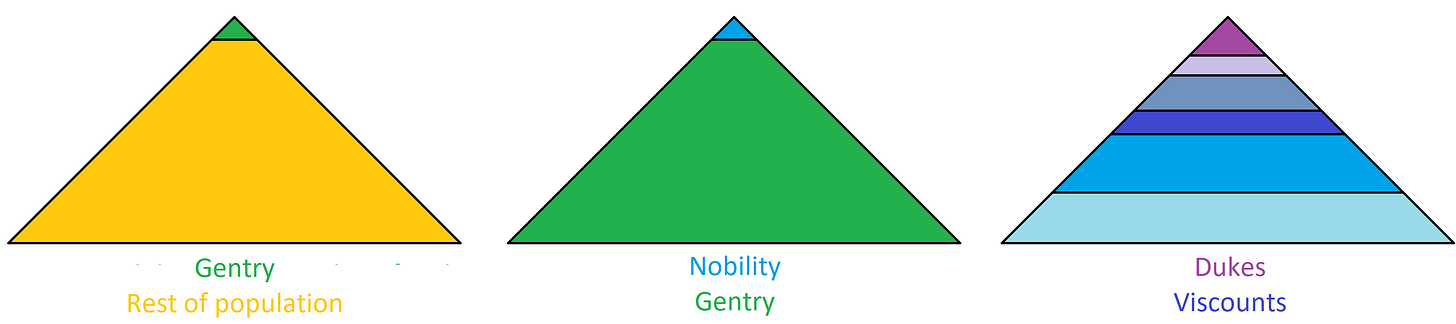

The social context in which Bridgerton takes place exacerbates the unrealistic nature of the ploy. Simon is a duke. Daphne is the sister of a viscount. Here are some useful (and roughly to scale) diagrams showing the semi-feudal hierarchy of Britain at the time to illustrate my next point. Simon’s social status is so stratospherically high that I can’t plot it on a single pyramid. I have to use three.

Simon belongs to the small dark purple capstone on that last pyramid. Daphne’s brother Anthony belongs to the narrow dark blue band in the middle of the third pyramid, while Daphne’s status as a mere relative is lower than Anthony’s status. There are over ten times as many nobles at or above Anthony’s rank as there are dukes, and probably around a hundred women comparable to Daphne’s social rank for every duke. For someone like Daphne (an eligible sister of a viscount), there are two main reasons not to try to court Simon as a husband:

Simon shows a very public disinterest in marriage. Some men are simply not the marrying type.

Simon is several tiers up in the hierarchy - far enough up that hierarchy that he may consider marrying a viscount’s sister beneath him.

Every time that Simon and Daphne display interest in each other in their pretend courtship, it’s evidence that Simon is considering marriage after all. It’s also evidence that he won’t simply turn up his nose at a noble of lesser status. The plan should backfire on Simon as Daphne’s emboldened peers (and their match-making mothers) eagerly emerge from the woodwork.

Now, what about Daphne’s male suitors? There’s a dueling scene from the Netflix show that will support my next point admirably. Here’s a still from it:

Nobles of those times, as a general rule, were prickly and dangerous creatures. Conflicts between nobles lead to a range of unfortunate consequences, ranging from violence to financial ruin. The setting of Bridgerton doesn’t change that, as conspicuously illustrated by a duel between Simon and Daphne’s brother. Any male suitor cutting in between Daphne and Simon would be risking the duke’s jealousy.

For any lesser nobleman or for members of the gentry, a conflict with a duke was something to be avoided. It would also likely be pointless: It’s difficult to imagine Daphne’s family favoring a lesser suitor over a wealthy and powerful duke, particularly when their daughter returns that interest in full measure. There are very rational reasons why Simon’s presence would deter Daphne’s other suitors.

However, even if Bridgerton had been set in modern-day America, Simon and Daphne’s plan succeeding still would have been bizarre. This isn’t how men typically behave here and now, either.

Who is attracted by what?

Could having a partner make you more attractive? This is a phenomenon called mate choice copying. Some studies have observed this type of behavior in various animal species, notably including guppies. There’s a certain annoyingly rational argument for why mate choice copying can work.

The argument goes like this: It’s genuinely hard to tell whether someone is a good partner. However, other individuals have more information. If someone has a partner, then they have already been inspected by that partner and found worthy.

Even if mate choice copying may seem like a rational strategy (and even if it is seen in some animal species), evidence for widespread human mate choice copying is lacking. In particular, mate choice copying by men as a group seems to be essentially non-existent; men seem to find the same women attractive whether or not they have partners.

This isn’t just my anecdotal experience, in other words; copying mate choices is rare among men. There is some evidence suggesting that single women engage in some amount of mate choice copying, although it’s not ironclad.1

Why does this mistake happen in the romance genre?

In my experience with the genre, it’s not unusual for romance writers to write stories where men copy the mate choices of other men. As a general rule, the romance genre features competition between men and decisions by women. There will be at least two men with a particular interest in the protagonist: A Mr. Right and at least one Mr. Wrong.2 At some point during the story, the protagonist will choose Mr. Right.3

If the Mr. Wrongs are the many men who reflexively copy Mr. Right’s choice of mate because his interest is social proof of the protagonist’s desirability, this is very convenient as a plot device. As far as I can tell, the fact that this is very unusual behavior for men doesn’t seem to bother most readers of the romance genre.

See particularly “Are all the taken men good?” and “Who’s chasing whom?” but also this meta-analysis, which tries to take into account publication bias.

This fact, as simple as it is, is probably the single largest reason that most movies marketed to women manage to fail the Bechdel test and pass the reverse Bechdel test.

The main exceptions to this are F/F, M/M, and “reverse harem” examples, but those are separate niche genres as far as marketing is concerned.