Tariffs & the neoliberal consensus

Part of a cross-topic series

Neoliberalism is a topic highly relevant to politics, but also involves a substantial bit of economics that isn’t fundamentally political. I’ll discuss the political side of it over on the MathIntee Political Post; the articles over here in the “Miscellany” department will deal with the economics itself. Neoliberalism refers broadly to a movement originating within economics to promote the use of free market economics in government policy. An expert consensus among economists emerged first, followed by a political consensus that emerged over a limited subset of neoliberal ideas.

In the United States (and many other developed democracies), purely domestic aspects of neoliberal economic policy remained politically contentious. A lasting consensus among political elites1 did emerge on two major topics related to foreign policy: Immigration and trade barriers. As part of a broader opposition to state barriers to economic activity, neoliberalism sought to make borders more porous, with both people and trade goods transiting freely.

Both parties were been broadly in favor of the reduction of trade barriers after 1945, though labor unions’ strong preference for protectionism meant that Democrats were slower to fully embrace free trade.2

Why tariffs are[n’t] bad

For various reasons, ranging from abundance of natural resources to technological development to the cost of labor and currency exchange rates, different countries frequently can produce comparable goods at different prices. In some cases, it may only be possible to produce certain goods in certain countries.3 The argument in favor of free trade is that specialization creates surplus.

If Country A is 20% better at producing widgets and Country B 20% is better at producing wingdings, then total production is 10% higher if Country A produces all the widgets and Country B produces all the wingdings and they trade freely, as opposed to each country producing their own widgets and wingdings.

Because successful industries tend to advance in terms of technology, processes, and human capital over time, success in a specific area tends to accumulate… as does failure. Country B’s declining widget industry would lose infrastructure, capacity, and expertise. The argument against free trade is that specialization creates dependence. Tariffs can create and maintain the existence and growth of an industry within a country.

This is not a new idea, and was generally held to do a fairly good job of explaining the non-military aspects of the rise and fall of economic powers by contemporary economists, historians, and policymakers from 1492 to 1945. Protectionist policy was widely credited by contemporaries as fueling the growth of the general industrial and economic power of Britain and later the United States.

What neoliberal economists argued was, in essence, that a rising tide would lift all boats, arguing that protectionist policy had substantial negative indirect effects that inhibited economic growth. It has become increasingly clear that this did not happen, and some of the prominent neoliberal economists of the age have started to admit that they were wrong about free trade.

From dependence to dominance

Dependence becomes particularly troublesome for economies that specialize in extracting resources. For example, in the 1500s and 1600s, the main export of Spain to was silver extracted from its New World colonies; this economic specialty, while nominally lucrative, did not lead to sustained growth, with Spain rapidly declining from Europe’s premier power to a second-rate power.

The Spanish dollar was still the most widely-circulated coin internationally through the end of the 1700s; for that reason, it became the basis for the American dollar minted by the newly-formed United States. From 1810 to 1821, Spain lost control of its main silver-producing colonies, which pushed Spain from a second-rate power to a third-rate one that further declined to a fourth-rate power by the time of the end of the dreadnought arms race.4

The problems linked to relying on extraction over production are well-documented in the literature on economic development. With regard to natural resources, this tends to be known as the resource curse. As seen in the example of Spain, the export of money is not appreciably more conducive to economic growth than the export of any other commodity. In the case of the United States, the main export within the period of the neoliberal consensus, beginning with the Carter administration in 1977, was (and still remains) the American dollar.

The inefficiency of “free” trade

Suppose that Country A and Country B both produce widgets. Per 100 widgets produced, Country A’s widget industry requires 1 hour of labor, 2 kilowatt-hours of electricity, 1 cubic meter of fresh water, and 2 kilograms of steel. Country B’s widget industry is less advanced and requires 3 hours of labor, 6 kilowatt-hours of electricity, 3 cubic meters of fresh water, and 3 kilograms of steel per 100 correctly manufactured widgets.

Which country has a competitive advantage in widgets?

In theory, Country A should have a huge competitive advantage in widgets. Since labor and energy costs tend to dominate, Country B’s widgets require three times as much labor and have three times the ecological impact. But if Country B’s currency is worth one third as much on the international currency markets, the two countries compete equally, and if Country B’s workers are willing to work for much lower real wages, free trade will destroy the more economically and ecologically efficient widget industry of Country A instead.

Deliberate disruption

Within a competitive market with entry barriers (and development of expertise and industry at scale is a real entry barrier for most markets), there’s a powerful anticompetitive strategy that has been used by “disruptive” players to great effect:

Offer products or services at a loss in order to compete better in the short term.

Wait for competitors to exit the market or be relegated to narrow niches.

In the absence of competition, increase prices (“price gouging”) or cut costs by reducing the quality of products or services (“enshittification”).

This basic business technique requires a willingness to lose money up front in order to secure higher returns later. This is sometimes referred to as a form of “predatory capitalism,” and typically, significant capital support is required to sustain losses on the scale required to disrupt an existing industry.5 The use of this technique on the national level typically involves government subsidies, which is why internal government subsidies are a hot topic in international trade.

The results

Everything that could go wrong with lowering trade barriers has gone wrong with the US decision to lower trade barriers with China. From the beginning of the Clinton administration to the end of the Obama administration, dollars and stable European currencies had roughly three to four times the value within China as they did internationally, partially as a result of deliberate manipulation of exchange rates by China.6 Additionally, the Chinese government offers very significant subsidies to key industries.7 Combining these two unfair trade advantages with lower real wages and environmental standards, Chinese manufacturers could compete with US and EU manufacturers while being grossly inefficient. Several decades of these practices have resulted in continued gains of expertise and infrastructure for Chinese manufacturers and significant losses of expertise and infrastructure for US and EU manufacturers.

Additionally, while it is not always obvious to consumers at the point of purchase, cheaply manufactured Chinese products are frequently held to lower standards of quality and safety, with flaws that are harmful to American and European consumers. This ranges from contamination with lead and other heavy metals to chips that enable espionage.

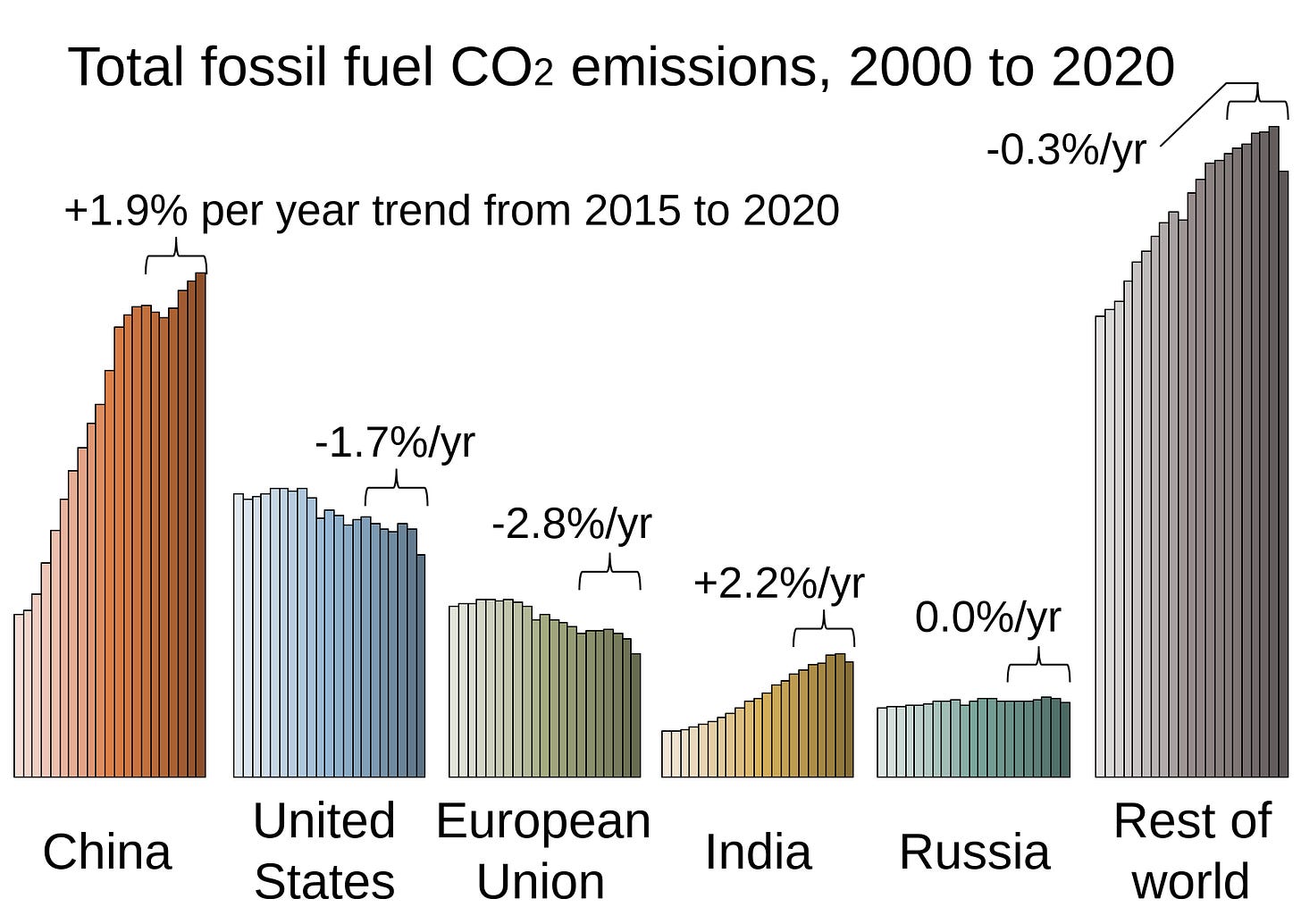

At this point, it is widely accepted that American manufacturing was, in fact, harmed by free trade in the neoliberal policy period, particularly as a result of trade with China, even by some neoliberal economists.8 Additionally, this has come at a substantial added environmental cost. China’s coal-fueled economy emits more carbon dioxide than the United States, European Union, and India combined. Free trade with China has been the leading cause of growth in carbon dioxide emissions in the 21st century.

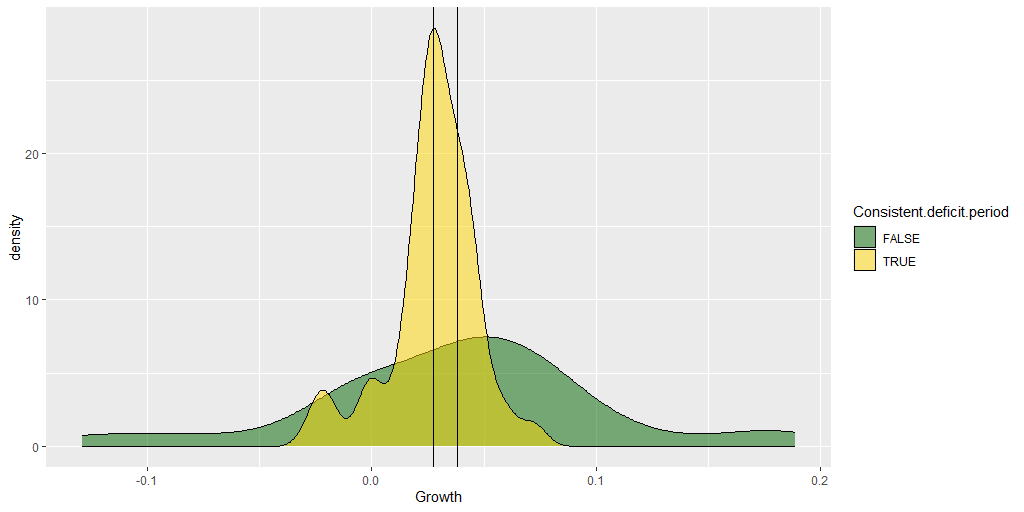

In spite of the theoretical strength of the claim that reducing trade barriers results in increased economic growth for both parties, there has been no increase in long-term GDP growth visible for the United States as a result of policies that resulted in a large and sustained trade deficit. In fact, the typical annual real GDP growth for the United States has declined from 4.4% in the 1929-1976 period to 2.8% in the 1977-2024 period. If lowering trade barriers had a positive effect on sustained US economic growth, then that effect was very small and dominated by at least one major economic policy mistake, likely one made sometime between 1965 and 1981.

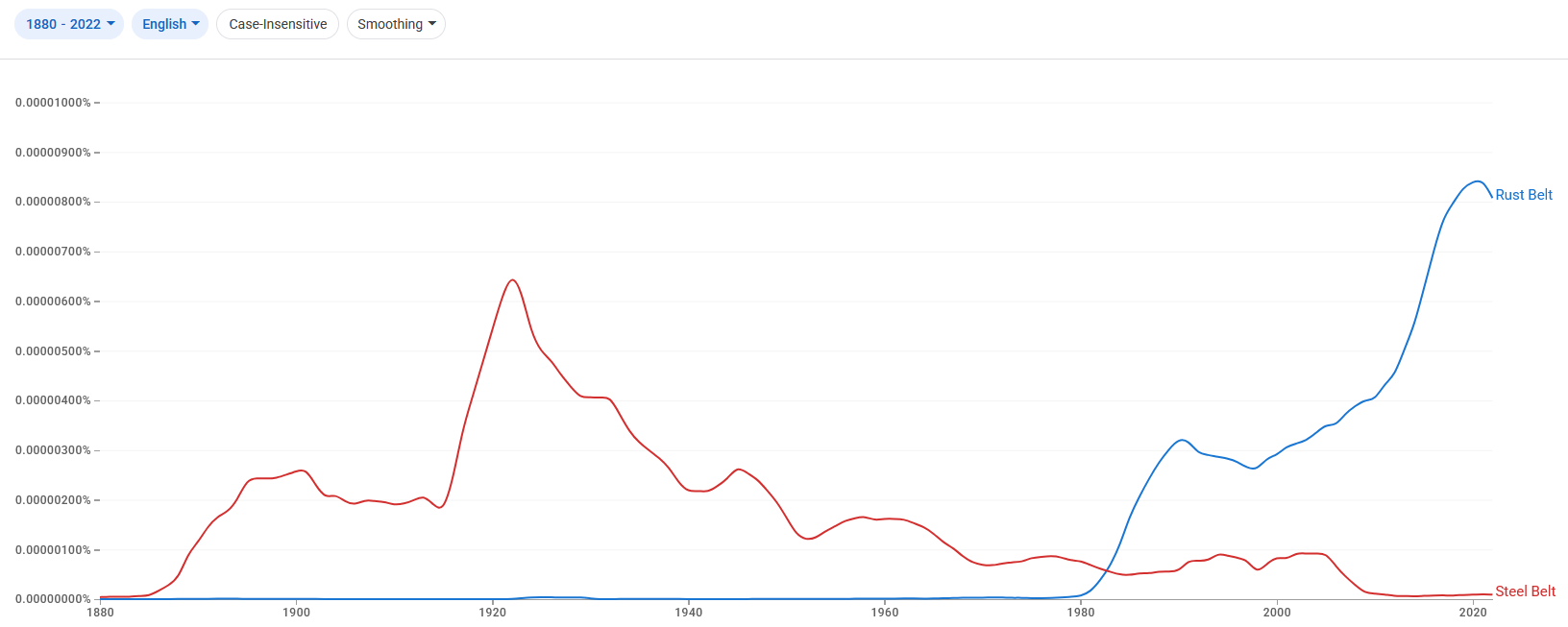

In addition to the overall reduction in national economic growth, broad economic malaise at the level of impacted cities, counties, and at least one entire major region of the country. The “Rust Belt,” formerly known as the “Steel Belt,” includes the eight Great Lakes states and substantial portions of several adjacent states; in spite of significant population declines associated with trade-induced economic malaise, this region still includes roughly a quarter of the population of the United States.9

While there were clearly both winners and losers when it came to the creation of massive trade deficits and the accompanying process of deindustrialization, industrial losses seem to have had broader regional impact than the financial gains reaped by the owners of companies that saved money by outsourcing. Labor is not as mobile as capital, and neither is most of the physical infrastructure involved with manufacturing.

In an environment with industrial growth across a region, downsized industrial workers could seek work in a related job not far away. Another manufacturer would be likely to take the place of the closed facility, either by buying the same site or opening a nearby site. In a deindustrializing environment, localized losses from individual factory closures were both devastating and persistent.

There are local positive feedback (“snowball”) effects associated with economic activity in general and employment in particular. The economic multiplier of manufacturing jobs is usually estimated as between half an order of magnitude and a full order of magnitude, meaning that the loss or gain of 1,000 manufacturing jobs tends to result in the total loss or gain of 3,000-10,000 jobs.10 Outsourcing jobs outsources many of the indirect US benefits of US jobs; it is entirely plausible that in some cases, gains of less than $1 million in profit by a US company resulting from outsourcing netted losses in total US economic activity greater than $10 million.

Recap and review

In theory, free trade leads to broadly increased economic growth and continual increases in the efficiency of production due to gains related to specialization. In practice, the US lowering trade barriers with China has been destructive for the affected sectors of the US economy, with no visible benefits in increased long-term growth. Instead, the era of large and consistent trade deficits has featured generally lower US economic growth. It has also been detrimental for the environment and national security.

If there has been a positive effect on the US economy from the growth of the trade deficit with China, it is small enough to be easily swamped by other factors. The complex nature of economic growth and malaise supports a skepticism of the degree to which the benefits of outsourced jobs can be predicted to be distributed equally between the involved countries. Whether this is a failure of free trade to create benefits for both partners or not depends on if currency exchange rates and industrial subsidies are taken into account.

The theoretical prediction of broad benefits and narrow detriments is difficult to reconcile with the observed reality that the detriments have been broad across a regional multi-state region, while net benefits on national economic growth have been effectively invisible. It is also difficult to reconcile with the historical support for the prior consensus: Protectionist policy was present throughout the growth of the UK as the first industrial superpower and the US as the second industrial superpower. Once we account for China’s de facto trade policies, it’s clear that something very similar is also associated with the growth of China as the world’s third industrial superpower.

Note, importantly, that this was not a broad consensus among the population as a whole, simply among elites. I’ll discuss that distinction in more detail on the MathIntee Political Post.

For example, the 1976 Democratic platform specifically called out dumping as an unfair trade practice. The Carter administration was, however, functionally in favor of lowering trade barriers with narrow exception, and by the time of the next Democratic administration (Clinton), the labor left was completely sidelined.

See particularly agricultural products that require certain climates, technology that is only available in one country, et cetera.

The Washington Naval Treaty required Italy, a third-rate naval power, to reduce its fleet down to 175,000 tons of dreadnoughts; Spain only had 45,000 tons of dreadnoughts.

Examples abound. Readers may be familiar with Walmart entering local markets and driving competing small retailers out of business, Uber’s loss-laden disruption of the taxi industry as it built up a user base and driver base, or Amazon’s long history of year over year losses on the way to building a near-monopoly on not only book sales but online retail.

China then also had labor costs that were even lower relative to the purchasing power of the yuan, thanks to significantly lower standards of living.

See https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/its-you-not-me-chinas-subsidies-and-global-trade-tensions/

See particularly Paul Krugman’s admissions.

Population of the Great Lakes states is currently about 85 million. Subtracting New York City is more or less balanced by adding chunks of New Jersey, Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Missouri.